Jordan and I crept toward the door frame. My rifle was raised over his shoulder, aiming down the end of the hall. In front of me, Jordan focused his sights on the entryway of the room to our left. He paused before exposing himself to anyone that might stand inside. I braked at his heels, keeping a steady aim down the hall. We paused until two more Marines joined us; training dictated that we enter a room in teams of four. A silent nudge, a knee to the back of my legs let me know two more had arrived. I gave Jordan the knee. He exploded beyond the frame. He took the left corner. I went right. We shouted bang at an enemy that was make-believe. Room clear, we all shouted. Exercise complete.

Our squad leader, Corporal Collopy, looked at the Omanis who had been watching our performance. “Just like that,” he said, “I want to see you guys run this through just like that.” The man my team and I thought was in charge instead started to rub his stomach. The other nine in the room followed suit. All at once, the Omanis headed toward the exit, rubbing their stomachs as they disappeared from site. The Americans stood, stunned. We had been tasked with conducting bilateral training with the Omani troops all morning, but not one hour into our exercises they had vanished. Our confusion turned to amusement as we realized their priorities: Training must wait. It was 9 a.m., time to eat.

At 9 a.m. the day before, I had been seasick and wanted nothing to do with food. My entire company, comprised of some 240 Marines, had departed the U.S.S. Carter Hall in a caravan of amphibious assault vehicles (AAVs). Each was built to fit 12 Marines, but we’d managed to fit 19 in mine. “Budget cuts,” the staff sergeant grumbled, insisting we “stuff one more in.” My AAV was one of the first to load, and after the other dozen had too, we’d plunged off the back off the ship and into the waters of the Arabian Sea.

The 19 of us had carried into the AAV our packs crammed with everything we’d need for the next two weeks. The space was so tight, so overfilled, that claustrophobia began taking hold of men who’d never experienced it. Fumes from burning diesel fuel billowed into the cabin. Each breath felt shorter, shallower than the one before it. Breathing became my singular focus. My watch read past noon; it had been hours since we’d last seen the sun, since we’d seen anything beyond the AAV’s steel walls. I closed my eyes, searching for some thoughts that would anchor my innards and quell my motion sickness. Saliva hiked up my throat. With nowhere else to throw up except on someone, I politely removed my helmet, sent my sickness into it, and placed it back onto my head. I’d have a canteen shower later, I reasoned.

Not three minutes after I’d puked, the AAV arrived on shore. Whatever incapacitated state we were in from seasickness and fume inhalation vanished. The AAV quickened on land and soon after came to a sudden halt. Two clicks. Both locks were undone. Like the sound of a roller coaster’s first ascent, the back gate began clanking its way to the ground. Before it had hit, we leapt off its edge and ran into the Omani desert.

We had practiced this hundreds of times before. Offload. And in a fury, assemble into a horizontal line. Without pause, begin maneuvering toward an enemy position in buddy pairs. One covers. The other moves.

McCarter covered for me. I began to battle the sand. Attempting to sprint, I pushed myself forward, but the ground proved fickle. The harder I pushed the deeper I sank. There was a 100-plus-meter assault ahead, and a few meters into it I was already out of breath. After I’d run far enough for McCarter to escape my peripherals, I lay down and began to cover.

A few hundred yards in front of us stood the sultan of Oman, Sayyid Qaboos Bin Said al Said; his entourage; and a host of U.S. officials. They were there to witness us, but I never got close enough to see anything but their silhouettes. This had become commonplace in our deployments. At times it felt like we were like an elaborate parade float being deployed across the globe.

Just as quickly as we’d run from the AAV, the exercise was over. In undramatic fashion, the photographer documenting the raid said to me, “I think you’re done.” Tactical formations morphed into small social circles as we waited for our tour buses to arrive to take us to an isolated outpost in the desert where we were to spend the next two weeks working alongside and helping to train our Omani counterparts.

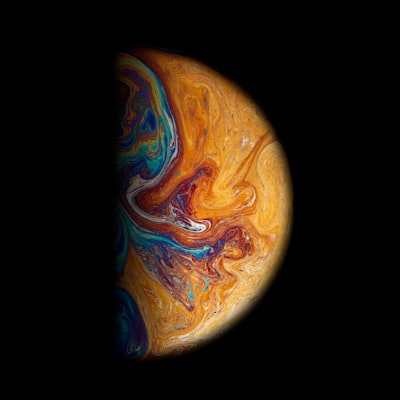

The geography was Mars-like: horizons broken by jagged, rocky, mountainous faces crusted with red sand. The sun burned so hot that I wondered if every would-be cloud was evaporating before it could form. As we pulled up to our outpost, I noticed from my window a small village in the distance. During the two-hour ride there I had seen every shade of red and orange, but I don’t recall seeing any blues or greens. No waterways or vegetation.

Left to our own devices, we all—both Americans and Omanis—resorted to sharing pictures on our phones and taking new ones together. We traded food with one another, our MREs for their freshly delivered pitas and hummus. Most military of all, we posed with and eventually shot each other’s weapons as a way to fill the silence left by our language barrier.

The first morning of training began, and we broke into our respective teams. One American team to every Omani team, consisting of about 12 people each. An American noncommissioned officer led the lesson, speaking in English but mimicking every action himself. The Omanis followed his instructions, albeit stumbling through halls while crossing each other’s line of fire. But their sloppy performance didn’t seem to bother them.

At precisely 9 a.m. Omani teams across the compound ran out of the training facilities and toward a silver truck making its way toward us from the open desert. Workers filled dozens of silver trays about half as wide as our rifles were long with hummus, surrounded with pita, and then handed a tray to each Omani team. The Omanis invited us to sit with them, cross-legged on the desert ground around the food.

Eating with the Omanis felt like eating at Grandma’s house—slow in pace and abundant in offerings. Every meal was an event unto itself; it was sacred, it was communal. Eating, an afterthought in the Marine Corps, now occupied a large portion of our training day, which seemed to fluster senior members of our unit. They had a long checklist of tasks they needed to complete. Chatting with the locals, showing pictures of life back home, and trading MRE packs for bites of hummus weren’t on that list.

I was never fond of their regimented decrees anyway; those lists always assumed that the serendipitous was for the unprepared. The Omanis, on the other hand, invited and welcomed the unexpected. To them, there was no day to seize; it was the other way around.

Our hellish commute to the country’s shores was eclipsed soon by the sweet, nutty flavor of the hummus they served and the community into which they welcomed us when they bid us join them on the ground to share in their meal. I felt that community again after lunch, when an Omani and I stood, backdropped by the red-crusted mountains, and warmly smiled together as we posed for a camera belonging to someone else whom I’ve never seen again. My rifle in his hands and his in mine.

That picture is somewhere, on a mantelpiece in a home in Oman, I hope. And, I hope, when someone asks who the American is posing with the man, he says, “I’m not sure who that is, but I’ll call him a friend.”

Editors Note: This article first appeared on The War Horse, an award-winning nonprofit news organization educating the public on military service. Subscribe to their newsletter